•

Author: David Moi •

∞

Breakthroughs don’t come every day, but the consequences of AlphaFold largely solving the 3D structure prediction problem has reshaped biology in profound ways. The sudden availability of protein structures for billions of proteins opens up many new possibilities. Last week’s two papers on the sequencing universe provide a compelling glimpse of the possibilities (here and here).

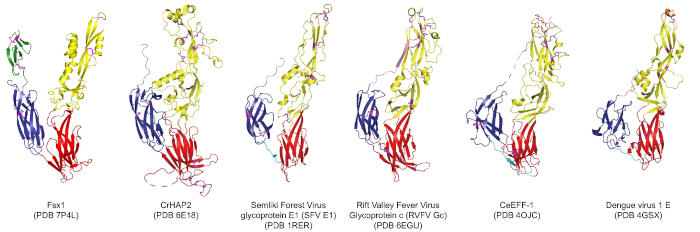

As someone who has been interested in tracing back the evolutionary origins of selected proteins—such as the cell fusion-mediating proteins fsx1 in plants, viruses, and archaea, or odorant receptors in insects—I have attempted to reconstruct phylogenies from structure in the past.

But I have faced two major issues:

Until AlphaFold came along, there typically wasn’t sufficient high-quality structure predictions as “starting material” to perform structure-based phylogenetics.

Even when I could obtain reasonably high confidence structures, the trees inferred from them were often met with skepticism—how reliable are these trees?

So now that high quality structure predictions are widely available, we could finally ask: are structures any good as starting material to infer trees? Specifically, how accurate are the reconstructed trees compared to sequences?

Today, we are super excited to report that structural phylogenetics works! What’s more, we found an approach that doesn’t just outperform traditional sequence-based methods for distant relationships; it also excels in resolving phylogenetic trees for closely related proteins. This post gives the gist of what we found—the full study is released as a preprint (1).

What’s the big deal with structural phylogenetics?

Before presenting our results, let’s take a step back. Why is structural phylogenetics potentially a big deal? Traditional phylogenetics, the study of evolutionary relationships among species or genes, has long relied on comparing the sequences of DNA, RNA, or proteins. While this approach has been immensely valuable, it does have its limitations. The primary challenge lies in the fact that the sequences of these biomolecules can change rapidly over time due to mutations and other factors, making it difficult to trace back their evolutionary history accurately when the divergence is very high. By contrast, proteins have unique three-dimensional structures that are intricately linked to their functions; these structures tend to change more slowly over evolutionary timescales compared to the sequences of the amino acids that make up the proteins since they are closely tied to the function of the protein.

In this particular example close to my heart, we can see structural homology between functionally homologous proteins at wide evolutionary ranges. The examples shown span plants, metazoans, viruses and archaea. They share virtually no sequence homology. Ref: (2)

When we set out to do our work, however, we were not at all sure that it would work, let alone outperform sequence based methods. On the one hand, there have been decades of intensive tool and model refinements for sequence-based approaches, unlike its structure-based counterpart. But also, complications related to structure, such as allostery, flexible regions, and functional constraints could conceivably confound the evolutionary signal that can be extracted from structures.

Evidence that structure-based trees can outperform sequence-based trees

We tested a few structural approaches, and settled on an approach reconstructing distance trees using Foldseek’s “local structural alphabet” approach, which was developed in the lab of our collaborator Martin Steinegger to search for similar structures very rapidly—by encoding local structure motifs in a 20-letter alphabet and repurposing highly optimized alignment software originally developed to align amino acid sequences (3).

Testing and comparing the quality of phylogenetic trees empirically is tricky business. Most comparisons are based on simulated data, or by comparing the fit of data to different models. But how to compare trees that are reconstructed from entirely different kinds of input data? Luckily, our lab has accumulated quite some experience in these kinds of empirical observations, used previously to compare the accuracy of alignment (4 and 5) or orthology (6 and 7) methods. We used an approach which compares the propensity of inferred trees to recapitulate the known taxonomy of the species from which the proteins are sampled from.

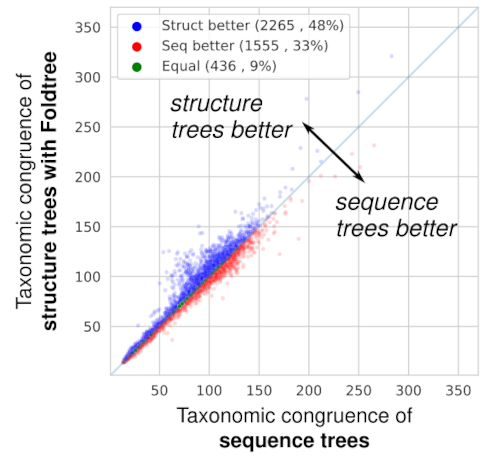

When comparing the taxonomic plausibility of thousands of trees derived from homologous protein families, Foldtree outperforms sequence-based phylogenetics. (In the paper, we show that after filtering the input set to families with high quality structures, the structural phylogenies perform even better!)

Amazingly, the trees we inferred in this way were more in line with the known taxonomy than those defined by sequence similarity! The input data can either be experimental crystal structures or AI structural models. Using good quality structures positively impacts the quality of the trees produced which means that as structural prediction methods get better, so will our structural trees.

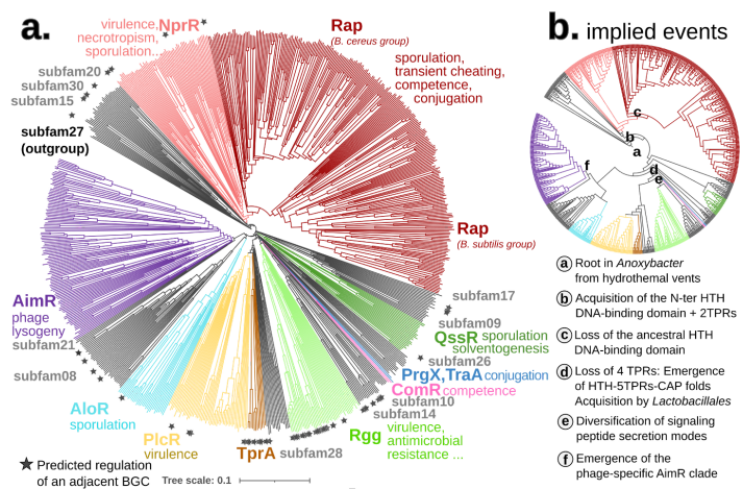

The RRNPPA family: a first unifying phylogeny for peptidic quorum sensing proteins

To put our method to the test, we focused on a particularly complex gene family - the RRNPPA quorum sensing receptors (8). These receptors play a pivotal role in enabling communication and coordination among gram-positive bacteria, plasmids, and bacteriophages for crucial behaviors like sporulation, virulence, antibiotic resistance, conjugation, and phage lysis/lysogeny decisions.

The complex evolutionary pattern of this family is revealed in its name. Before AI structures, new homologs were previously only detectable after having been crystallized and each subfamily was added piecemeal to the overall picture, resulting in their particularly long acronym. As the family expanded researchers also attempted to piece together its evolutionary history, using a diverse set of methods, some of which relied on structural analysis. Using Foldtree we decoded the evolutionary diversification of these genes, shedding new light on their intricate history.

Compared to the sequence-based phylogeny, the Foldtree reconstruction of the RRNPPA family’s history is remarkably parsimonious. Several events such as domain architecture changes or transfers to the viral world appear only once in the tree.

Foldtree: infer a structural phylogeny for your favorite protein family

To make it easy to try this approach, as well as facilitate methodological improvements, we are releasing this new approach as an open source tool we call Foldtree. It’s available for download on GitHub (https://github.com/DessimozLab/fold_tree). Try it on your favorite protein family and let us know how it performs!

Exciting new research directions

High-accuracy structural phylogenetics has the potential to uncover deeper evolutionary relationships, elucidate unknown protein functions, and even refine the design of bioengineered molecules. The evolutionary histories of protein families in the viral domain, the start of eukaryotic life and the role of asgard archaea as well as the evolution of the prokaryotic mobilome are just a few cases where the fast pace of evolution has confounded sequence-based analyses and could be revisited. We believe this work represents an important step in investigating how structures are polished by the processes of evolution and how we can use this signal to peer further into the past than ever before.

References

Moi D, Bernard C, Steinegger M, Nevers Y, Langleib M, Dessimoz C. Structural phylogenetics unravels the evolutionary diversification of communication systems in gram-positive bacteria and their viruses. bioRxiv 2023.09.19.558401; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.09.19.558401

Moi D, Nishio S, Li X, Valansi C, Langleib M, Brukman NG, et al. Discovery of archaeal fusexins homologous to eukaryotic HAP2/GCS1 gamete fusion proteins. Nat Commun. 2022;13: 3880. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31564-1

van Kempen M, Kim SS, Tumescheit C, Mirdita M, Lee J, Gilchrist CLM, et al. Fast and accurate protein structure search with Foldseek. Nat Biotechnol. 2023. doi:10.1038/s41587-023-01773-0

Tan G, Gil M, Löytynoja AP, Goldman N, Dessimoz C. Simple chained guide trees give poorer multiple sequence alignments than inferred trees in simulation and phylogenetic benchmarks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015. pp. E99–100. doi:10.1073/pnas.1417526112

Dessimoz C, Gil M. Phylogenetic assessment of alignments reveals neglected tree signal in gaps. Genome Biol. 2010;11: R37. doi:10.1186/gb-2010-11-4-r37

Altenhoff AM, Dessimoz C. Phylogenetic and functional assessment of orthologs inference projects and methods. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5: e1000262. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000262

Altenhoff AM, Boeckmann B, Capella-Gutierrez S, Dalquen DA, DeLuca T, Forslund K, et al. Standardized benchmarking in the quest for orthologs. Nat Methods. 2016;13: 425–430. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3830

Bernard C, Li Y, Lopez P, Bapteste E. Large-scale identification of known and novel RRNPP quorum sensing systems by RRNPP_detector captures novel features of bacterial, plasmidic and viral co-evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2023. doi:10.1093/molbev/msad062

•

Author: Yannis Nevers & Christophe Dessimoz •

∞

Proteins are fundamental to all life forms, dictating the complex biochemical interactions that maintain and drive the existence of every species. The functionality of a protein hinges on its structural domain organization, and the protein’s length is a direct manifestation of this. Given that every species has evolved under varying evolutionary pressures, one would intuitively expect protein length distribution to differ significantly across species.

Well, we report in a paper just published in Genome Biology that this is not the case.

Unexpected Homogeneity in Protein Length Distribution

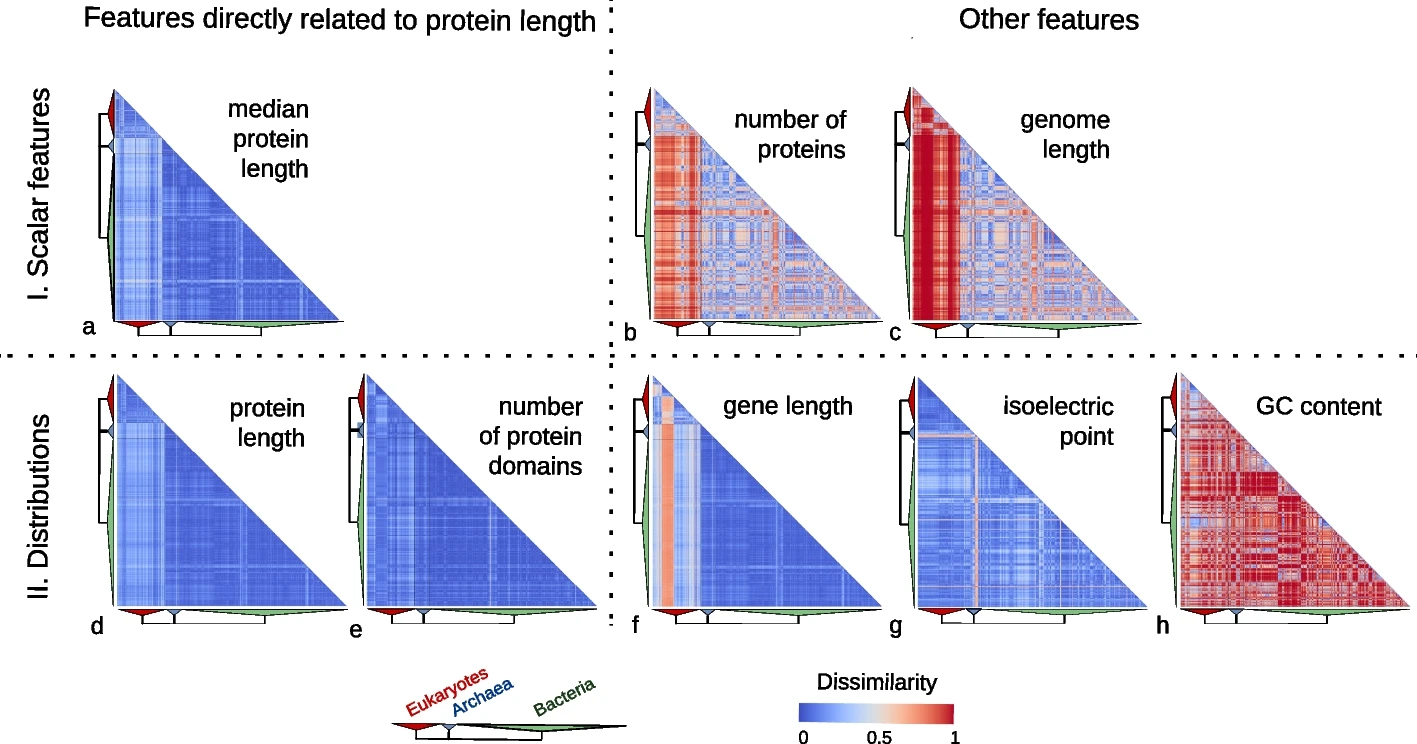

In our study, we examined the protein length distribution across 2,326 species encompassing 1,688 bacteria, 153 archaea, and 485 eukaryotes. Counter to expectations, we observed a striking consistency in protein length distribution across these species. Though eukaryotic proteins were somewhat longer, the variation in protein length distribution was notably low compared to other genomic features such as genome size, gene length, number of proteins, GC content, and isoelectric points of proteins.

Features directly related to protein length are much more conserved than other features.

Exceptions: Errors or Biological Peculiarities?

We did note a few atypical cases of protein length distribution, but these were typically due to inaccuracies in gene annotation: no well-annotated model species displayed enrichment in small proteins, and those with a high number of small proteins were more likely to have incomplete or fragmented genome annotations.

Indeed, the outliers tended to include many more genomes scoring low in BUSCO quality score. The only exception we observed was the prevalence of longer proteins in the Ustilago fungal genus and the Apicomplexa phylum, known for their intracellular parasitic lifestyles.

This suggests that the actual variation in protein length distribution might be even smaller than what we reported. Hopefully, resequencing and reannotation efforts will help solve this issue in the future: we already noticed a few species getting updated proteomes where the length distributions gets more similar to the typical one!

A Universal Selection Force at Play

The startling uniformity of protein length distribution across diverse species suggests a strong, universal selective pressure, maintaining a high proportion of the coding sequence within a specific length range. In the discussion part of the paper, we articulate a number of potential explanations, but these remain highly speculative.

More positively put, the evolutionary forces behind the uniformity of protein distribution and their potential impact on fitness remain exciting areas of exploration!

Protein Length Distribution: A New Criterion for Gene Quality?

This observation led us to propose the use of protein length distribution as a new criterion of protein-coding gene quality upon publication. Considering that the overabundance of spurious proteins could potentially bias downstream analyses, this quality measure could aid in identifying and rectifying annotation errors. We also encourage everyone to take a look at this simple criterion when selecting proteomes for comparative genomics analysis.

Story behind the paper

The basic premise of the paper, exploring protein length distribution across the tree of life, may seem straightforward at first glance. Not quite. It started as part of Yannis’s PhD in Odile Lecompte’s lab in Strasbourg—and a few questions: what are the characteristics of the thousands of publicly available proteomes? How to decide which to include in large scale analyses? It took another three years of Yannis’s postdoc, with about half of that time spent in the peer-review process.

Perhaps the most revealing testament to the depth of this work is the supplementary PDF, a 68-page document filled with detailed data and analyses. Moreover, anyone interested in the peer-review history of our paper can delve into the 18-page record available here.

The journey is the reward, they say; well in this instance, we are quite happy to have reached our destination!

Reference:

Nevers, Y., Glover, N.M., Dessimoz, C, Lecompte, O. Protein length distribution is remarkably uniform across the tree of life. Genome Biol 24, 135 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-023-02973-2

•

Author: Christophe Dessimoz & Fritz Sedlazeck •

∞

We just published a method to build phylogenetic trees directly from raw reads, bypassing time-consuming steps such as genome assembly. This post gives the short story and the backstory. In particular, find out below what Read2Tree has in common with “Smoke on the Water” from the band Deep Purple.

In biology, phylogenetic trees are everywhere. They help us understand the relationships between species, genes, or cells—how they evolved, and how they’re related.

The sequencing revolution provides the raw material to infer phylogenetic trees, but building state-of-the-art phylogenetic trees requires tedious steps from read curation, de novo assembly, gene annotation, ortholog identification to tree inference, which can take many months to run—millions of CPU hours invested in this process are not uncommon—and specialised knowledge to oversee this process.

That’s where Read2Tree comes in. Our new approach to tree inference bypasses the usual steps of genome assembly, annotation, and orthology inference. Instead, it uses existing knowledge of the protein sequence universe to directly reconstruct comprehensive sequence alignments from raw sequencing reads.

The approach is vastly faster than traditional methods and in many cases more accurate—the exception being when sequencing coverage is high and reference species very distant. Read2Tree is also flexible, working with genome and transcriptome, short and long reads, and sequencing coverage as low as 0.1x.

We were encouraged by the buzz the Read2Tree manuscript elicited on bioRxiv last year, and are delighted it has now been published in Nature Biotechnology.

What is Read2Tree good for?

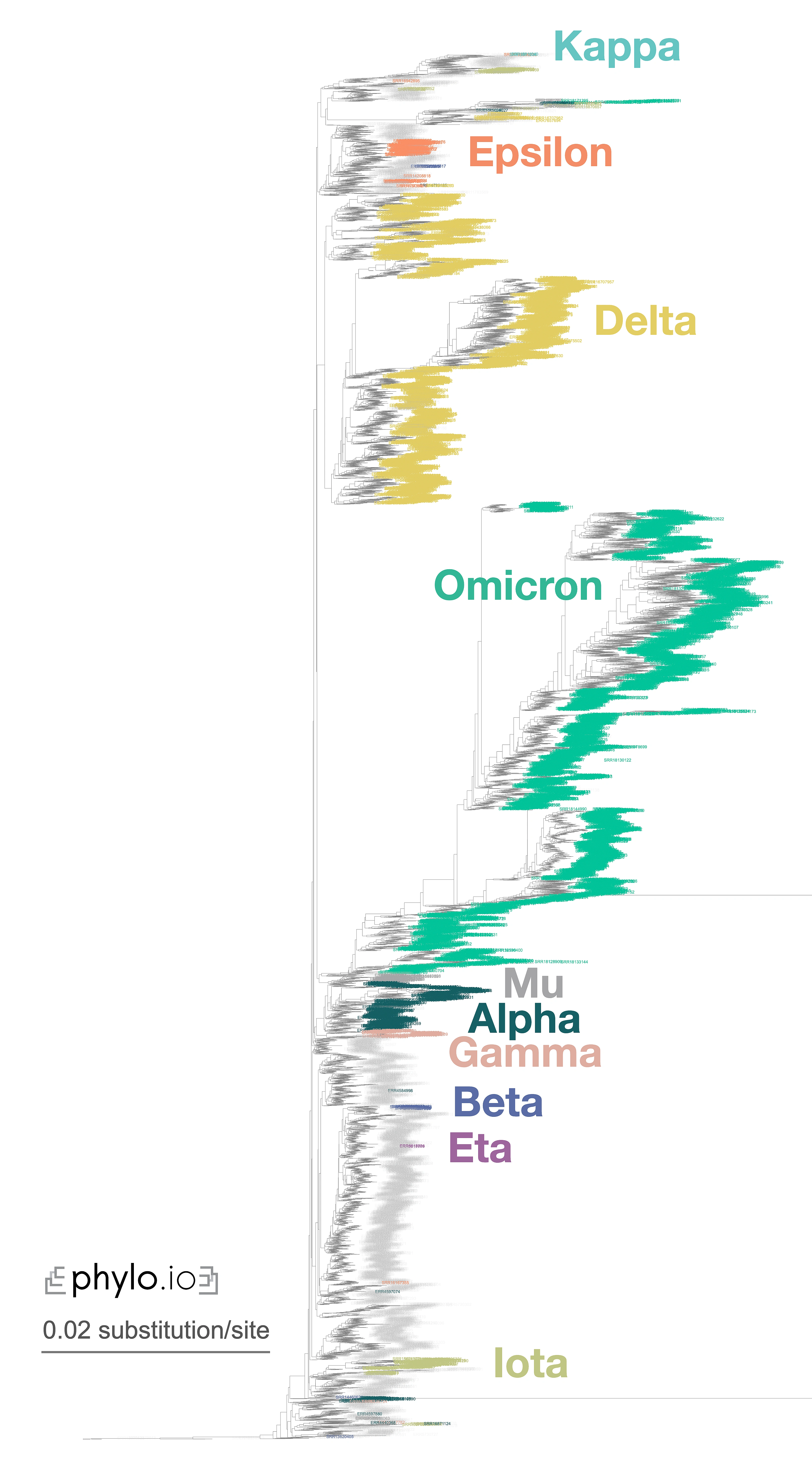

A nice illustration of Read2Tree’s potential was the reconstruction of a phylogeny of coronaviruses, which processed on the same tree diverse Coronaviridae sequences as well as 10,000 raw SARS-CoV-2 datasets from the Short Read Archive. The reconstructed tree was consistent with the lineage classification obtained from the UniProt reference proteomes, accurately recovering the main coronavirus genera and all subgenera (Figure 1). At the same time, the same phylogeny accurately clustered the sequences according to CDC variants of concerns classification. These results demonstrate the versatility and scalability of Read2Tree, making it suitable for both zoonotic surveillance and human epidemiology.

Figure 1—Zoomed-in display of a tree inferred using Read2Tree on 10,283 samples whole genome SARS-CoV-2 samples. Classification in colour was obtained from [https://harvestvariants.info](https://harvestvariants.info), where grey leaves are unclassified according to the CDC label. The colour clustering shows that the Read2Tree-based tree recovers consistent classification. Click on the tree to see it full screen.

The ability to reconstruct phylogenetic trees from raw reads has additional advantages. Some genomes are deposited with poor or even entirely absent protein annotation sets. Processing genomes directly from raw reads can avoid this limitation and also decrease biases that arise from relying too heavily on specific reference genomes. Although some efforts have been made to “dehumanize” non-human great ape genomes, other clades still face similar biases that can be significantly reduced by processing raw reads.

Who might find it useful?

We think Read2Tree will be especially useful for small labs with limited bioinformatics expertise and computational resources, allowing them to perform state-of-the-art phylogenomics on particular species or environments of interest.

But it’s not just small labs that can benefit from Read2Tree. Large consortia can also use it to regularly update their trees as new genomes are sequenced. This is especially important as more and more projects around comparative genomics are underway, such as the Earth BioGenome, the Darwin Tree of Life, or the European Reference Genome Atlas projects.

In addition, Read2Tree’s ability to infer trees from much lower coverage than traditional methods means it can also be useful for quality control early in the process. This makes it a valuable tool for environmental and metagenomic applications, especially when combined with genome binning techniques.

Overall, Read2Tree is a powerful method for inferring phylogenetic trees directly from raw sequencing reads. We hope it will help make phylogenetic tree inference faster, more accurate, and more accessible to a wider range of researchers.

What’s next?

Now that the introductory Read2Tree paper is published, we are excited to explore new potential applications that we haven’t been able to tackle so far. For instance, we have already received inquiries from researchers interested in using Read2Tree for ancient DNA applications or for monitoring systems that require fast turnaround time and low coverage.

Moving forward, we have two main goals. First, we aim to expand Read2Tree’s capabilities to handle multi-species samples, which will enable an even broader range of applications in the metagenomics field. While long-read applications may offer the most benefit, we are confident that Read2Tree’s ability to perform well with short-reads will also prove valuable in detangling multiple species.

Secondly, we plan to explore the use of Read2Tree in single-cell sequencing. This rapidly growing field involves sequencing individual cells, including cancer cells, and analysing their genetic information. Given Read2Tree’s ability to operate with low coverage levels (down to 0.2x), we believe it could facilitate fast and accurate characterization of tumour or cell evolution.

We hope that Read2Tree will help streamline and democratise comparative genomics analyses. We are excited to see how researchers will apply this tool to further advance our understanding of genetics and evolution.

What’s the backstory?

Both of our labs (Fritz Sedlazeck’s and Christophe Dessimoz’s) have been collaborating for many years, and we’ve always enjoyed exchanging ideas even though our research interests are quite diverse. One of our interests over the years is how to combine our expertise in sequence analysis and ortholog comparison to develop new methodologies and gain new insights into biology.

It was during one of Fritz’s visits to Christophe’s lab in Lausanne, Switzerland, that we started brainstorming ideas for a project that led to Read2Tree. Our goal was to overcome the limitations and bottlenecks of comparative genomics. We had some amazing cheese risotto, and the beautiful scenery fueled our discussions further (Figure 2).

Figure 2 — Fritz alleges that the epiphany of Read2Tree took place with this view from his hotel room in Montreux, Switzerland, during a collaborative visit to Christophe’s group. It’s not entirely implausible, considering this very view [inspired the song “Smoke on the Water” by Deep Purple](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smoke_on_the_Water#History).

David Dylus, the first author, was convinced that it was possible to bring our ideas to life, although he did not anticipate how much time and effort it would take (Figure 3). Even after he moved on to a new role in the pharmaceutical industry, he continued to work on Read2Tree after regular work hours. And when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, we had to face additional challenges, such as maintaining regular meetings and pushing the manuscript forward while not compromising on quality. We also faced technical issues, such as hard disk crashes and cluster updates that led to data loss, but David hang on.

Completing the paper was not an easy task, and one of the biggest challenges was organising and identifying all of the SRA data sets, including those related to yeast and COVID-19. Despite these challenges, we were able to bring the project to completion. It was a special joy to present the work at ISMB 2022, where Fritz and Christophe had the wonderful opportunity to meet in person, and we continued to discuss our work while enjoying good food and drinks by beautiful Mendota lake in Madison, Wisconsin.

In summary, nice food and lakeside views were instrumental in the making of Read2Tree.

Figure 3 — First author David Dylus performing on stage (centre, crouching) on the occasion of SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics’s 20th anniversary—a period of rapid progress in the development of Read2Tree. Though no-one is entirely certain, rumour has it that David is miming “sipping a cup of tea while looking into the distance”, in line with our theme of sustenance, inspiring landscapes, and scientific progress.

Note this blog post was first published on the Nature Communities blog here.

Reference

Dylus, D., Altenhoff, A., Majidian, S. et al. Inference of phylogenetic trees directly from raw sequencing reads using Read2Tree. Nat Biotechnol (2023). doi:10.1038/s41587-023-01753-4.

•

Author: Charles Bernard •

∞

This year, the MCEB international conference was held in Switzerland for the first time in its history.

During five days, from June 26th to 30th 2022, experts in mathematical and computational evolutionary biology

from all over the world exchanged about their passion in Chateau d’Oex,

in the heart of the welcoming mountains of the regional natural park of Gruyeres.

Here is a little summary on this annual not-to-be-missed event for evolutionary biology aficinionados.

The edition 2022 of the international MCEB conference brought together a hundreds of scientists

from diverse disciplines and at different stages of their career,

from PhD students to world-renown senior scientists.

During five consecutive days, the Chateau d’Oex has hence been the improbable scene of inspiring exchanges

about evolution between mathematicians, computational biologists, evolutionary biologists, ecologists,

epidemiologists and cancer biologists.

View from the conference venue (left) and cheese making social activity (right).

In total, 6 one-hour talks and 20 short talks were given to present

epistemological perspectives, recent methodological advances and challenges yet to be addressed

for reconstructing the evolutionary history of the genes, genomes, populations and species

observed then and today on Earth.

As a mirror of the truly interdisciplinary nature of the event, a wide range of phylogenetic structures

have been discussed during these five days.

Networks of gene flows, phylogenetic trees, or genealogical trees predicted by coalescent theory

were on the menu of this year.

Experts specialized in introgressive events such as horizontal gene transfers or endosymbioses

provided insights on the methods and challenges to model reticulate evolution.

With this respect, an inspirational talk was given on how ghost lineages that went extinct in the past

but nonetheless exchanged some DNA with ancestors of extant species could mislead our interpretation

of the directionality of gene flows within phylogenetic networks.

Lectures on the theoretical advances that were made throughout the last 50 years in the reconstruction

of gene and species phylogenetic trees were then given by world leaders in the field of phylogeny.

In particular, they provided mathematical evidence that contrary to what is practiced today

to reconstruct species trees, neither the consensus tree of several gene trees

nor the tree inferred from the concatenated alignment of these genes

actually give a good approximation of the phylogeny of the different species encoding these genes,

which highlights the urgent need to pursue methodological efforts to better model species evolution.

On shorter evolutionary timescales, numerous mathematical models to infer geneological trees

of human populations or cancer cell lineages were also presented during the conference.

Poster session (left) and group photo (right).

Finally, a strong focus was placed this year on methods for coupling phylogenetic inferences with phenotypical,

ecological, archaeological, geographical, epidemiological and medical data in order to study

how traits or diseases evolved across space and time.

Striking examples of these integrative analyses were provided by methodologies to retrace with accuracy the evolution

of the recent Sars-Cov2 and MERS-Cov pandemics over time and space.

In addition to these talks of exceptional scientific quality, two poster sessions animated

by junior researchers and students took place during the conference and were truly appreciated

by every participants for the scientific excellence of the posters and the conviviality of the moments.

Overall, through five days of scientific presentations, poster sessions, dinners, parties

and social activities such as hiking in the Alpes or visiting a cheese factory,

scientific exchanges and informal talks were fostered and allowed to create news bonds within this community of researchers.

The MCEB 2022 conference was a great success as it enabled a diversity of scientists from all over the world to meet,

exchange on their work and build new collaborations!

•

Author: Christophe Dessimoz •

∞

Life as an academic is varied and busy. Students sometimes believe that all we do is teach. In fact, we do quite a few other things. Here’s my 2016 in numbers.

- number of papers published: 10

- number of paper rejections: 7

- number of books edited: 1

- number of grant proposals submitted: 8

- number of research contracts negotiated with the industry: 2

- number of blog posts: 5

- number of tweets: 474 (66% were retweets)

- number of YouTube videos: 1

- number of papers reviewed: 24

- number of papers edited: 3

- number of grants reviewed: 3

- number of PhD theses examined: 2

- number of emails received (excluding spam and mailing-lists): 12,695

- number of emails written: 4,377 (!)

- number of minutes videoconferencing on GoToMeeting: 13,236 (!!)

- number of Geneva-London-Geneva roundtrips: 12

- number of meetings with >50 attendees co-organised: 6

- number of seminars hosted: 4

- number of conferences attended: 3

- number of talks given: 11

- number of semester-long courses organised: 2

- number of hours lectured: 32

- number of 2000-word student papers marked: 47

- number of summer students supervised: 4

- number of overnight retreats attended: 4

- number of work Christmas dinners attended: 3

- number of annual reports written: 3 (this does not count)

- number of Tête de Moine eaten at lab celebrations: 4

- number of times moved home: 0 (noteworthy since we moved 5 times in the preceding 5 years…)

I wish you, Dear Reader, all the best in 2017!

•

Author: Tunca Doğan •

∞

Note: the “Life in the Lab” series features interviews of interns and visitors. This post is by our second 2016 OMA Visiting Fellow Tunca Doğan, who spent a month with us earlier this year. You can follow Tunca on Twitter at @tuncadogan. —Christophe

Please introduce yourself in a few sentences.

My name is Tunca Doğan. I received my PhD in 2013 with a thesis study in the fields of bioinformatics and computational biology where we developed methods for the clustering of the protein sequences using unsupervised machine learning techniques (Dogan and Karacali, 2013). I’ve since been working as a post-doctoral fellow in the EMBL-EBI, UK under the Protein Function Development team (UniProt Database) leaded by Dr Maria Martin. Here I’m developing new tools and methods for the automated functional annotation of protein records in the UniProtKB using a variety of features including domain architectures (Dogan et al., 2016). I’m also conducting research in the field of computational drug discovery. As of 2016, I’m also affiliated to the Department of Health Informatics, METU, Turkey both as a senior research fellow and a faculty candidate.

Why did you choose to apply to the OMA visiting fellowship programme?

The team behind OMA is world-leading in the field of phylogenomics, and they authored many highly cited publications in this area. Moreover, OMA is considered to be one of the most reliable and comprehensive resources offering phylogenomic information on various species. I’ve applied to this programme in order to develop my knowledge in phylogenomic research, particularly about the OMA production. My specific research aim was to investigate if and how the information in OMA can be utilized in order to increase the coverage and the quality of the automated functional annotation of proteins in the UniProt database.

Discussions on UNIL campus with Leonardo de Oliveria Martins, Surag Nair, Clément Train, David Dylus and Tunca Doğan (from l. to r.)

What project did you work on during your visit?

The project I worked on had two sides: 1) investigating novel ways of quality checking of the data produced in the OMA pipeline (especially HOGs) using the Domain Architecture Alignment and Classification (DAAC) method I previously developed in UniProt; 2) investigating the use of OMA groups and HOGs to propagate the functional annotation between the (homologous) member proteins of the same clusters/classes.

Was there any highlight or low point you’d like to share?

It was a great experience for me both professionally and socially. I’ve learnt a great deal in just one month and we still keep our collaboration with the continuation of the abovementioned project. Everyone I met in the group: Christophe, Adrian, David, Leonardo and Clement were all knowledgeable, helpful and friendly that I had great time during my stay. It was a great pleasure to meet and to work with them all…

UNIL/EPFL campus is just beautiful, at the shores of lake Geneva. The campus is also well-equipped for all possible needs. This was also my first time in Switzerland and I was enchanted by the beauty of this country… The only downside for a foreign visitor could be the expensiveness of life in Switzerland, which was also manageable with a little prior investigation and planning.

Do you have any practical tip for future OMA visiting fellows?

I definitely recommend any researcher (at PhD or post-doc level) that has an interest in phylogenomics to apply to this programme. You’ll learn a great deal and have a good time at the same time. Also (for the foreigners) do not forget about travelling around this beautiful country in your spare time…

Editor’s note: If you are interested in the OMA visiting fellowship programme, consult this page.

References:

Doğan T, & Karaçalı B (2013). Automatic identification of highly conserved family regions and relationships in genome wide datasets including remote protein sequences. PloS one, 8 (9) PMID: 24069417

Doğan T, MacDougall A, Saidi R, Poggioli D, Bateman A, O’Donovan C, & Martin MJ (2016). UniProt-DAAC: domain architecture alignment and classification, a new method for automatic functional annotation in UniProtKB. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 32 (15), 2264-71 PMID: 27153729

•

Author: Rosa Fernández García •

∞

Note: We are rebooting our “Life in the Lab” series, which features interviews of interns and visitors. This post is by our inaugural OMA Visiting Fellow Rosa Fernández García, who spent a month with us earlier this year. You can follow Rosa on Twitter at @Rosamygale. —Christophe

Please introduce yourself and your research interests.

I received my bachelor’s degree in Biology (major in Zoology) at Complutense University in Madrid, Spain. I got my master’s and PhD at the same university with a thesis about phylogeny and phylogeography of cosmopolitan earthworms. After that, I moved to the lab of Prof. Gonzalo Giribet at Harvard University where I was a postdoc during 3 years and a Research Associate for another year. In January 2017, I’ll move to Barcelona to work as a Research Fellow in the lab of Dr. Toni Gabaldón at the Center for Genomic Regulation.

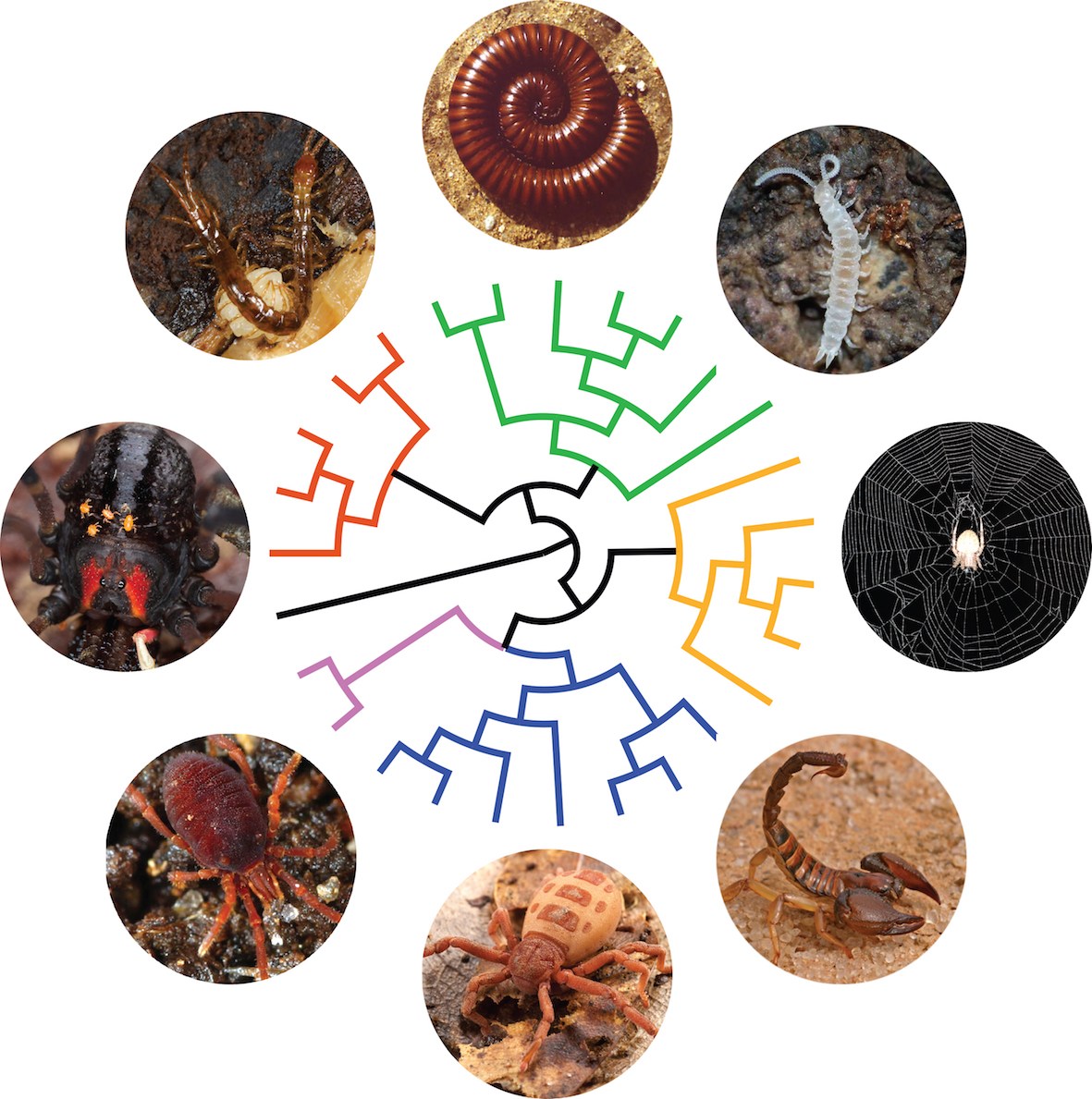

My research addresses fundamental questions about evolution in invertebrates: in other words, I am fascinated by how, when and where biodiversity took its form, and why it is maintained. My main two animal groups of interest are terrestrial annelids (oligochaetes) and (pan)arthropods, particularly the earliest branching lineages and most scientifically neglected groups (chelicerates and myriapods).

How did biodiversity took its shape? Resolving the tree of life. Macroevolutionary patterns are generally what we see when we look at the large-scale history of life. It encompasses the grandest trends and transformations in evolution, such as the origin of bilateral animals or the radiation of arthropods. In order to understand how lineages are related to each other, I study macroevolutionary patterns in several groups of invertebrates through phylogenetics and phylogenomics. I currently lead a fruitful line of research dealing with phylogenomics of myriapods and chelicerates, having optimized protocols to sequence successfully single individuals of the rarest and smallest arthropods. We are getting closer to resolve the Arthropod Tree of Life!

Artist’s rendition of the Arthropod tree of life

When and where? I tried to understand the mode and tempo of animal diversification patterns through the integration of phylogeography, biogeography and paleogeography.

Why? Comparative transcriptomics and genomics is a very powerful tool to shed light on very interesting evolutionary questions, such as arthropod terrestrialization - one of my favorite new lines of research.

Why did you choose to apply to the OMA visiting fellowship programme?

Orthology inference is one of the key steps in phylogenomics. I had been using OMA for a few years and I wanted to learn how I could use it more efficiently in my ongoing projects.

What project did you work on during your visit?

My project focused on optimizing OMA runs for some big and challenging data sets that I was having problems with. Also, I was interested in learning how I could exploit hierarchical orthogroups for comparative genomics studies in arthropods.

Rosa and David Dylus at coffee break (photo by Arthur Dessimoz)

Was there any highlight or low point you’d like to share?

It was a great experience to be in the Dessimoz lab for a month. As a systematist with relatively limited bioinformatic background, it was absolutely great to exchange ideas with computer scientists interested in the same scientific problems but with a completely different perspective that mine. It was a very enriching experience.

Do you have any practical tip for future OMA visiting fellows?

One month was not enough for me, so try to stay longer if your project is ambitious. And ask Christophe to bring a Tête de Moine cheese in your last day, it’s delicious!

Editor’s note: If you are interested in the OMA visiting fellowship programme, consult this page.

References:

Fernández R, Laumer CE, Vahtera V, Libro S, Kaluziak S, Sharma PP, Pérez-Porro AR, Edgecombe GD, & Giribet G (2014). Evaluating topological conflict in centipede phylogeny using transcriptomic data sets. Molecular biology and evolution, 31 (6), 1500-13 PMID: 24674821

Fernández, R., Hormiga, G., & Giribet, G. (2014). Phylogenomic Analysis of Spiders Reveals Nonmonophyly of Orb Weavers Current Biology, 24 (15), 1772-1777 DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.035

Fernández R, & Giribet G (2015). Unnoticed in the tropics: phylogenomic resolution of the poorly known arachnid order Ricinulei (Arachnida). Royal Society open science, 2 (6) PMID: 26543583

Novo M, Fernández R, Andrade SC, Marchán DF, Cunha L, & Díaz Cosín DJ (2016). Phylogenomic analyses of a Mediterranean earthworm family (Annelida: Hormogastridae). Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 94 (Pt B), 473-8 PMID: 26522608

Fernández R, Edgecombe GD, & Giribet G (2016). Exploring Phylogenetic Relationships within Myriapoda and the Effects of Matrix Composition and Occupancy on Phylogenomic Reconstruction. Systematic biology, 65 (5), 871-89 PMID: 27162151

Sharma, P., Fernandez, R., Esposito, L., Gonzalez-Santillan, E., & Monod, L. (2015). Phylogenomic resolution of scorpions reveals multilevel discordance with morphological phylogenetic signal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 282 (1804), 20142953-20142953 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2014.2953

Rosa Fernandez, Prashant Sharma, Ana LM Tourinho, & Gonzalo Giribet (2016). The Opiliones Tree of Life: shedding light on harvestmen relationships through transcriptomics BioRxiv DOI: 10.1101/077594

•

Author: Christophe Dessimoz •

∞

The new academic year brings a big change to our lab. I am moving to the

University of Lausanne, Switzerland, on a professorship

grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation. The

generous funding will enable us to expand our activities on computational

methods dealing with mixtures of phylogenetic

histories. Lausanne is a hub

for life sciences and bioinformatics so we will feel right at home there—indeed

we have already been collaborating with several

groups

there. I

join the Center for Integrative Genomics and the

Department of Ecology and Evolution. I also look

forward to reintegrating the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. At a personal

level, this marks a return to a region in which I grew up, after 16 years in

exile.

However, I keep a joint appointment at UCL, where part

of the lab remains. I’ll be flying back regularly and keep some of my

teaching

activities. UCL is a very special place—one which would be too hard for me to leave

entirely. For all the cynicism we hear about universities-as-businesses, the

overriding priority at UCL clearly remains on outstanding scholarship. My

departments (Genetics, Evolution, Environment and

Computer Science) are both highly collegial and

supportive. Compared to the previous institutions I have worked for, the

organisational culture at UCL is very much bottom-up. The pervasive chaos is

perceived as a shortcoming by some, but it’s actually a huge competitive

advantage—one that leaves ample room for initiative and flexibility. One

colleague once told me that I could build a nuclear reactor in my lab and no

one would ask a question—provided I secure the funding for it of course…

So how are we going to manage working in two different sites? Well, the

situation is not new. We have had a distributed lab for several years and have

developed a system for remote collaboration. Currently, we have lab members

primarily based in London, Zurich, Ghent, and Cambridge. Our weekly lab

meeting and monthly journal club are done via videoconference (with

GoToMeeting). I try to have at least fortnightly 1:1

meetings with all remote members. During the day, the lab stays in touch via

instant messaging (using HipChat). We have shared code

(git) and data (sshfs) repositories. We tend to write collaborative papers

using Google Docs (with Paperpile as reference

manager). Importantly, we have a lab retreat every four months where we meet

in person, reflect on our work, and

have

fun. We

supplement this with collaborative visits as needed. The system is not

perfect—please share your experience if you’ve found other good ways of

collaborating remotely—but overall it’s working quite well.

•

Authors: Ed Chalstrey, Jan Koch, Clement Train & Lucas Wittwer •

∞

On 25-27 May 2015, the lab attended the 4th international ‘Quest for Orthologs’ conference held at Center for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona, Spain. The following blog entry is a summary of the experiences had at the conference by Ed Chalstrey, Jan Koch, Clement Train, and Lucas Wittwer, who are interns and master’s students in the Dessimoz lab.

Quest for Orthologs (QfO) is a meeting of groups working on orthology detection and phylogenomic databases, with an aim to improve and standardise orthology predictions. This meeting was part of a series of conferences beginning in 2009, which have successfully brought together a community of researchers with shared goals. These goals included collaboration on benchmarking and the sharing of reference datasets.

As short project students in the group, QfO gave an excellent opportunity for those of us based at UCL to meet some of our colleagues from ETH (in Zurich) and Bayer CropScience (in Ghent) in person for the first time and to make contact with other scientists working in the field of ortholog prediction.

As young scientists, some of the most important questions we face are: Will I be able to explain my project to established scientists and discuss it with them? Will I be able to understand the work of other scientists, even if their research topic falls outside my area of expertise? How can I have new ideas and be inspired to contribute to an area of research I’m new to? For us, most of whom had not attended a conference before, QfO was the perfect place to begin answering these questions.

The conference involved talks from each of the research groups and a poster session for students to display their contributions. Each of the postdocs and PhD students in the Dessimoz lab gave a short talk to introduce their posters, as well as one of us (Clement).

Clement: “The talk and the poster were the great practice for us to increase our communication skills by presenting to an audience composed of experts in related topics. This enabled us to adapt our talks depending of the kind of people we had in front of us and exchange ideas with other people during a constructive conversation. Also, attending talks on the many fields related to our work (orthology) was an amazing experience as interns, both in discovering new things and helping us in our own project with new ideas and other ways of thinking.”

QfO was a great opportunity for us to meet scientists that have worked in the field for many years and from all over the world. We were able to benefit from their experience and the advice they gave us after talking with them about our own research projects, gaining a different perspective to that of our usual supervisors and colleagues. One of the discussions had by Jan with two researchers from Switzerland may even lead to a potential future collaboration; they were interested in DLIGHT, a program that was developed by our group.

As well as discussing our current work, the conference also gave us the chance to think about future work opportunities and network with established scientists. One of the highlights for us was meeting Eugene Koonin and Sergei Mekhedov from the NCBI at the conference dinner. We had an amusing chat (about topics not necessarily related to orthology!) and an enjoyable evening. They even invited us to visit them at the NCBI!

All in all, we greatly benefited from our participation in the QfO conference.

•

Author: Anna Sueki •

∞

Note: this is another interview in our series “Life in the Lab”, which gives unedited accounts of students who have spent time with us. —Christophe

Please introduce yourself in a few sentences.

I am Anna Sueki, 3rd year Biochemistry student at UCL. I did my summer internship at Dr. Dessimoz’s lab during summer 2014. I’m originally from Japan, but grew up in Singapore and Germany.

Why did you choose to join the lab?

During my second year, I took a module called “Computational Biology” and I really enjoyed learning programming and other computational aspects in biology. Dr. Dessimoz was one of the lecturer for that module, and since I found his lectures interesting, I applied to his lab for this summer internship.

What project did you work on (and for how long)?

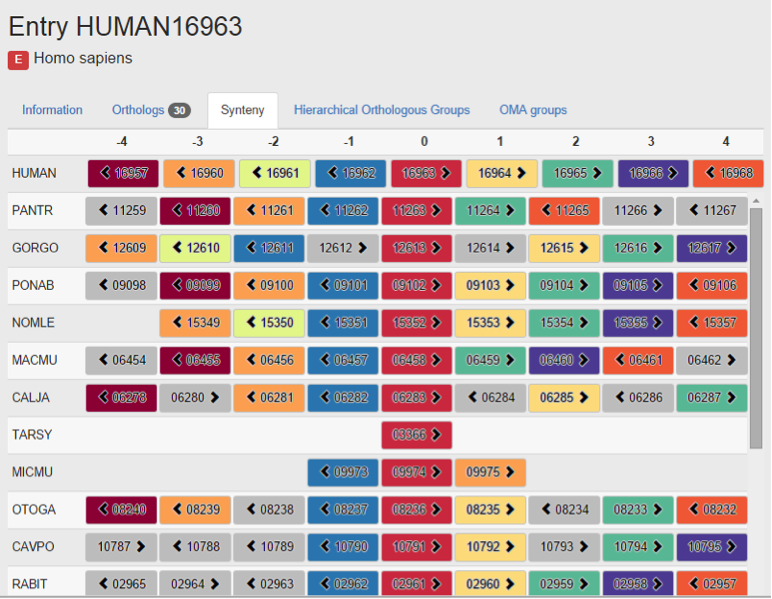

My project was “Synteny visualisation in the OMA browser”. This was for the new release of the OMA browser, and I created the new synteny viewer function within the browser to show neighbouring genes of the entry gene and its ortholog relationships. I worked for 3 months (from June to September 2014) during my summer vacation.

What came out of it?

With the help of other members in the lab, I could produce the synteny viewer function, and it will be implemented in the new OMA browser. Also, explanation of this new function and an example was included in the paper for new OMA release.

Other than this actual project outcome, I learned about how computers and their systems work, programming of Python, and how to use Python’s web framework Django.

New synteny viewer in the OMA Browser

Was there any highlight or low point you’d like to share?

Personally, I enjoyed the lab retreat in Zurich a lot. It was nice to see the members in Zurich who I saw only through video meeting every week. Also I got many helps from Zurich members through the chatting system, especially Adrian and Clement.

What is your overall impression and would you do it again?

I really enjoyed my time in Dr. Dessimoz’s lab, and I learned a lot during these three months. I started without barely any knowledge in computer science but through this summer, I found out that I like learning coding and other computational skills. If I can achieve another chance, I would love to work with Dr. Dessimoz and other members again!

The Dessimoz Lab

blog is licensed under a Creative

Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License.

The Dessimoz Lab

blog is licensed under a Creative

Commons

Attribution 4.0 International License.